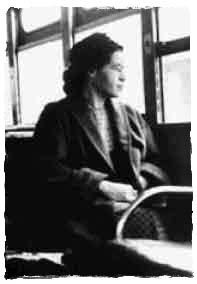

1913 – 2005

May we all be worthy

of your defiance and your bravery.

Every now and then, for no reason I can figure out, a chill floats down onto me.

Cold settles on my shoulders, and when I try to shrug it off, it only slides farther down my body, until I am shrouded to the ankles in chilly fog.

Through this fog it is difficult to see clearly the people I love. Their faces are blurry and vague. Are they smiling, or laughing? The music in me becomes distant and muffled, and I can’t make sense of it. Like the sound of a band in the gym when you are smoking in the parking lot, it has no clarity, only a dull thumping, and I can’t find the melody, can’t catch up with the beat.

The things I do seem useless. All my projects – the protest song, the ongoing writing project that is this blog, the books I want to read, the music I am trying to record, the computer I plan to build, the places I want to go – who cares? Not me, not now. Would it make any difference if I did them or not?

Sometimes I go outside late at night and stand in the deserted street and look at the sky. Even through the haze and the lights of this big city and the fat October moon I can see a few stars, and I expand into the universe and I feel huge and empty and weightless with the the stars and after a while I can see the little guy down there on the street, so small, his arms waving toward heaven, and I think What do you want?

But I get no answer. From the street, from the stars, I get no answer.

White bread. Bad for me. But my weakness.

Today I found a half-loaf of white bread in the lunchroom. I was walking past when I saw a brown paper bag on one of the tables. Curious as always, I went in and took a peek. In the bag was the half-loaf. A round, bakery-style loaf of heavily processed bleached white flour, gluten and yeast, the kind of bread that has no nutritional value and starts turning into paste as soon as you put it in your mouth, then goes in and sticks to various parts of your insides, possibly forever.

I turned and quickly headed for the door, but the bread started calling my name. One little taste won’t be missed, I thought. So I went back and took a little bite.

My whole addictive system throbbed with pleasure. It was moist and soft, slightly chewy. Not a gourmet experience. More of a pig-in-mud experience. There was no butter, no cheese, no spread, and none was needed. There was also no bread knife.

I ripped off another piece of it with my bare hand, this one about the size of a small eggplant, and began stuffing it in my mouth. I held the remnants behind my back in shame and stuck my head out the door. No one was in the hall in either direction, so I hot-footed to my office, still pushing more of the glorious gluten into my face.

I got crumbs all over the floor in my office, but I didn’t care. I haven’t had bread like this in years. Get behind me, Worthless Loaf! Cease your siren song! Luckily I only had an hour of work to go before I could get the hell out of there, and back to my home, where I keep plenty of emergency celery.

Yum.

Are you the Mystery Cougher? Am I?

Today at 5:30 in the afternoon I heard the new Ricola commercial on the radio. I immediately pushed the button to switch to another station, and they were playing the same commercial. Weird, I thought, and hit the button again, and heard the same commercial again. Thinking I had somehow switched back to the original station, I hit the button again, and heard the commercial for the fourth consecutive time. These guys are really carpet-bombing us.

I was forced to figure out what it was about, and now I share with you:

Ricola makes cough drops, and they have always had strange advertising. I remember one on TV that involved some guy in quaint Swiss folk garb blowing on a 20-foot Swiss horn in a subway car, for example.

But the current campaign is truly bizarre. They have a Mystery Cougher, a man (or maybe a woman, they hint) who goes around coughing near people. If you hear him and offer him a Ricola cough drop, BINGO! You win money, up to a million bucks! If this works, we will all have to buy at least one package of Ricola cough drops, and start offering them to anyone who coughs around us, because who can take a chance on losing a million dollars? I’m assuming this is a nationwide campaign, so that’s a lot of damn cough drops. But would you accept a cough drop from a stranger? Would you offer one? Would people call Homeland Security on you if you did?

Looks like we may find out.

I trudge up the hill, alone in the dark.

This is the hill that the kids came to in their cars all those years ago, after football games, after Friday night dances, and I can almost hear the giggling and the urgent exhortations. Boys and girls parking beneath the oil derricks on this desolate piece of land, a giant hump right in the middle of the city, lit by no light but the moon, disturbed by no sound but the grind and screech of the big oil pumps, sucking life from the hill like huge iron mosquitoes. The oil had mostly dried up ten years earlier, but a few pumps remained to make sure that every drop was sucked out. A lot of the derricks were still there, too, standing silent watch, ten-story weathered wooden lattices, relics of the drilling, no longer needed but not worth tearing down. The pumps huddled indifferently under their bases, pumping always.

Once you got to the top and parked the car, the view was breathtaking. This was before the streetlights were orange, and in the night the city stretched like a glittering sequined sheet all the way to the harbor, and the black ocean beyond could have been the very edge of the universe. You felt like you were flying, just standing there next to the car. I did, anyway. I might have been the only kid who actually saw the view, because even though I had a car, I never took a girl up there, to watch the submarine races, as we used to call it. I cruised it enough times, though, to know what it looked like, and I felt good up there alone, above it all, needing no one.

It’s the steepest hill in the region, and back then the pavement ended halfway up. Above that were just the twisting oil company access roads, dirt and gravel. No one lived up here, the derricks your only witness, except for the occasional squad car. Tonight as I walk, high-priced apartments line the freshly blacktopped roads, cheaply built boxes put here to cash in on that view, contoured into fancy-looking architectural shapes through the magic of styrofoam. The hill has been remade, too, primped up with landscaping and terraced lots for the houses, cut sharply into the earth. The derricks are all gone now, and the few stubborn oil pumps are hidden artfully behind stands of palms and local shrubs.

Once there was a nightclub at the very top of this hill. You’d drive along the deserted road in total darkness for a quarter-mile, you’d be aware of music playing somewhere, then abruptly you’d come upon a dirt parking lot lit by a few bare floodlights on makeshift poles. At the far end of the lot was the nightclub, looking like an island of corruption. An impossibly garish neon sign blinked

DANCING.

The hill had its own police department, company security left over from the oil boom, and maybe that’s why the ID check at the door was not as rigorous as in the city below. For whatever reason, my friends drank there. Come on, Jones, the Lost Boys would say. They don’t care how old you are, as long as you’re spendin’ money. I didn’t see the fascination, and my fear of being thrown out was greater than my curiosity. I regret not going now, like so many things I didn’t do.

In the end, I played in the band there, so I saw the place anyway, from the inside. I was too afraid to go in there just to see if I could fool them, but it was OK to do it if they paid me. I was not old enough to be working there, but no one ever asked about that. On stage I was a screaming showoff, shouting the blues like I meant it, but during the breaks I disappeared into the shadows, the better not to get found out and ejected. The irony of this behavior eluded me at the time. Strangely, none of my smartass friends ever saw me perform there, and eventually I came to wonder if they really ever went there.

Now I live in the shadow of the hill, and tonight I cruised it, like I used to. I don’t know what happened to the old roads. They’re not merely gone – their spirit is erased. There are guardrails and asphalt where once there were abandoned jalopies and loose gravel. Somehow, intersections and street signs have been contrived. The seedy nightclub has been razed and at the top, there’s a little park, a lookout point with a stone wall around the perimeter, concrete benches and a statue. Even the park is two-thirds paved.

I leave the car a few blocks down and walk up toward the park. I wonder if any of the boys and girls who used to make out here in cars are living in these town homes, and if so, are they living with the ones they made out with? When I reach the top there are teenagers there, some couples, some groups. I’m pretty sure I know what has drawn them here, but they are safely contained in the bright enclosure, so their natural urges are stymied.

I stand at the stone wall, and the view is still breathtaking. The streetlights below are mostly orange now – is that what makes it less magical? Or is it that we know each other better now, the city and me? I own a piece of it, and it owns a piece of me. I think about flying over the city, like I did when I was a kid, but instead I just feel like I’m falling, and in fact I stagger back from the stone wall, catching myself before I actually take off. After that I leave the teenagers behind, as I always have, and go back to my car.

When I get there, I stand by the side of the road and take in the unauthorized view for a final moment. The city has grown. It is so big and bright now that it eclipses the stars and dims the moon. It is full of living, dying, trying, crying. And out past the harbor, the very edge of the universe seems closer than ever.

I was spellbound for two hours last night watching Martin Scorcese’s Bob Dylan documentary “No Direction Home.”

Maybe it’s because of my age — I was sort of there for the original events — but I couldn’t take my eyes off the screen. What a thrilling time that was, and how exciting it must have been for young Bob and the others who speak in this film: Dave Van Ronk, Maria Muldaur, Suze Rotolo (she’s on some of the old LP covers), Liam Clancy, Joan Baez, Mavis Staples – more than I can recall. New York City, 1963. The baton is being passed from the Beat Generation to Dylan and his circle. There are a million places to play. Dylan and the others are sponges, soaking up the old guys like Woody Guthrie, and each other, learning new music, new styles, new voices, and actually saying something in their songs. It’s not a concert show, but I was still fascinated and hugely entertained. Catch Part Two tonight (Tuesday, September 27, 2005) on PBS. In Los Angeles it’s on KCET, Channel 28 at 9:00 PM, but I think it’s a national presentation. This is history, folks, but fresh enough to feel contemporary. Most of the original players are still with us.

While I’m at it, I just want to say “Hurray!” to National Public Radio’s coverage of the ongoing hurricane disasters on the U.S. gulf coast. These stories, mostly on the afternoon news show “All Things Considered,” are precious documents. Heart-warming, heart-wrenching, visceral, surprising, maddening, informative, in ways I just don’t see the mainstream media doing. The 79-year-old woman who lived alone, floating inside her one-story home on her Stearns and Foster mattress for eight days before she was rescued (“It must have a lot of wood in it…”). The New Orleans pump station worker caught by NPR’s reporter dozing on the job – because he had not deserted his post for three weeks nonstop. The man who sent his family to safety and doesn’t even know where they are, while he stayed behind to assist whomever he could in his 9th Ward neighborhood. This is why we need public radio and television, my friends. Tune in and see for yourself.

As always, my heart is yours alone. And again, I might owe some of you an apology. Please forgive my transgressions. I am socially inept, and I should know better.

Avast, me hearties!

Did ye know it’s Talk Like a Pirate Day? Skuttle me skippers if it ain’t! Arrrgh…

I’ve been feeling funky, and not in a good way, since the Katrina disaster.

(Click here ![]() to play background music.)

to play background music.)

It’s none of my business, really. We all have our disasters to cope with – hurricanes, typhoons, tornadoes, floods, earthquakes, suicide attacks, not to mention our personal tragedies. Most of the time we are simply aware that shit happens, and we grieve, we deal, we move on. That’s what I do.

But there are facets of this particular mess that linger and sting past the usual spoil date, and as I go through my daily motions I have this nagging heaviness that makes everything seem off, somehow. I am too scattered to make a lot of sense of my feelings. I don’t get paid to make sense. So here’s a list of thoughts:

I don’t know if this is all out of my system yet. I hope it is. I want to move on. Life is precious, and so damned short. If you clicked on the “play” button at the top of this (and if your computer is capable), you’ve been listening to Paul Simon’s “Take Me to the Mardi Gras:”

C’mon take me to the mardi gras

Where the people sing and play

Where the dancing is elite

And there’s music in the street

Both night and dayHurry take me to the mardi gras

In the city of my dreams

You can legalize your lows

You can wear your summer clothes

In New OrleansAnd I will lay my burden down

Rest my head upon that shore

And when I wear that starry crown

I won’t be wanting anymoreTake your burdens to the mardi gras

Let the music wash your soul

You can mingle in the street

You can jingle to the beat of the jelly roll

As always, my heart beats only for you, the things we have lost, and those we still seek.